Today's post is a gem that someone had anonymously emailed me off forum on the theme spiritual gifts. I read this entire book years ago and it is still insightful, powerful, biblical, and edifying. This is not casual fair, but rich nourishment for the soul. In this discussion on spiritual gifts, John Owen offers biblical clarity and a theological practicality that cuts through the dense fog surrounding this issue with the laser light of God's Word (Heb. 4:12-16).

Today's post is a gem that someone had anonymously emailed me off forum on the theme spiritual gifts. I read this entire book years ago and it is still insightful, powerful, biblical, and edifying. This is not casual fair, but rich nourishment for the soul. In this discussion on spiritual gifts, John Owen offers biblical clarity and a theological practicality that cuts through the dense fog surrounding this issue with the laser light of God's Word (Heb. 4:12-16).

This will take some time to read. It will require dedication, some serious study, a Bible, and a willingness to lay aside personal bias's and subjective experience in order to be a faithful hearer and doer of the Word. If all you want to do is sound off on this issue of spiritual gifts (cessationism/continuationsism) never having to dig into the Scriptures as to what they teach about these things... there are plenty of other blogs willing to accommodate you. Not here. We live in difficult days beloved, and this is a time for sober thinking that is constrained, compelled, and conducted by the Word of God--not reactive rabbit trails.

My heartfelt gratitude to Dr. J.I. Packer for navigating us through the deep theological waters of John Owen's teaching. "A Quest for Godliness" is a worthy volume that any Christian home library should have on its shelf. I would encourage you to a purchase this excellent tome today.

I highly commend this article to all who have ears to hear.

It is desirable to delimit explicitly the area within which our study of Owen will move, for there could be false expectations here. To many Christians today, the phrase ‘spiritual gifts’ suggests a wider range of questions and concerns than it did to the Puritans. Throughout the century that separated William Perkins’ pioneer ventures in pastoral theology (The Arte of Prophesying, Latin 1592, English 1600; The Calling of the Ministerie, 1605) from Owen’s Discourse, Puritan attention when discussing gifts was dominated by their interest in the ordained ministry, and hence in those particular gifts which qualify a man for ministerial office, and questions about other gifts to other persons were rarely raised. Preoccupied as they were— and as their times required them to be—with securing high standards in the ministry, and educating layfolk out of superstition and fanaticism, the Puritans had both their minds and their hands full, and modern questions about laymen’s gifts and service were given less of an airing than we might have expected or hoped for. Two such questions in particular may be noted here, since they bulk so large in present-day debate.

First, how should we evaluate ‘Pentecostalism’ (the so-called ‘charismatic movement’) in modern evangelical life?

The Pentecostal movement, in both its denominational and its interdenominational forms, claims to be in essence a renewal of neglected but authentic elements in Christianity—namely, the gifts of tongues, prophecy, and healing. (The details of the claim vary from group to group.) Can the Puritans help us to assess these claims? Only indirectly, for there was no such movement in Puritan times. Seventeenth-century England did not, to my knowledge, produce anyone who claimed the gift of tongues,2 and though claimants to prophetic and healing powers were not

______________________________

1In his Inquiry concerning…, written after the publication of Stillingfleet’s sermon On the Mischief of Separation (preached 2 May 1680) and before Stillingfleet’s larger work, The Unreasonableness of Separation, appeared in the following year (Owen, Works, XV:221f, 375). Owen refers to his Discourse of Spiritual Gifts as already written (p 249). In the preface to The Work of the Spirit in Prayer, published in 1682, he mentions a treatise on spiritual gifts as something he proposes to write (IV:246). This indicates that The Work of the Spirit in Prayer, which follows Causes, Ways and Means of Understanding the Mind of God (published 1678) in the sequence of Owen’s treatises on the Holy Spirit, was written perhaps three years before it was published, since by 1680 its promised successor had already been completed. The Discourse of Spiritual Gifts is in IV:420-520.

2The only Protestant tongue-speakers in the seventeenth century appear to have been the Camisards, Huguenot refugees who fled to the Cevennes after the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685. In other ways the Camisard movement was unquestionably fanatical; see Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (1957), sv, and literature there cited.

unknown, particularly in the wild days of the forties and fifties, the signs of enthusiasm (fanatical delusion) and mental unbalance were all too evident.3

It was partly, no doubt, Owen’s experience with such people that prompted him to write, of the class of ‘gifts which in their own nature exceed the whole power of all our faculties’ (in which class he puts tongues, prophetic disclosure, and power to heal), that ‘that dispensation of the Spirit is long since ceased, and where it is now pretended unto by any, it may justly be suspected as an enthusiastical delusion’.4 But does this mean that, like B.B. Warfield,5 Owen would rule out a priori all possibility of renewal, for any purpose, of the charismata which were given in the apostolic age to authenticate the apostles’ personal ministry and message? Owen nowhere says so much, and it would be rash to ascribe to him this dogmatic a priori negation, which, as has often been pointed out, is not inevitably implied by any biblical passage. Rather, it may be supposed (though this, in the nature of the case, can only be a guess) that were Owen confronted with modern Pentecostal phenomena he would judge each case a posteriori, on its own merit, according to these four principles:

1. Since the presumption against any such renewal is strong, and liability to ‘enthusiasm’ is part of the infirmity of every regenerate man, any extra-rational manifestation like glossolalia needs to be watched and tested most narrowly, over a considerable period of time, before one can, even provisionally, venture to ascribe it to God.Owen was deeply concerned to bring out the supernaturalness of the Christian life, and to do justice to the Spirit’s work in it, but whether he could have felt close sympathy with any form of modern Pentecostalism is a question about which opinions might differ.

2. Since the use of a person’s gifts is intended by God to further the work of grace in his own soul (we shall see Owen arguing this later), the possibility that (for instance) a man’s glossolalia is from God can only be entertained at all as long as it is accompanied by a discernible ripening of the fruit of the Spirit in his life.

3. To be more interested in extraordinary gifts of lesser worth6 than in ordinary ones of greater value; to be more absorbed in seeking one’s own spiritual enrichment than in seeking the edifying of the church; and to have one’s attention centered on the Holy Spirit, whereas the Spirit himself is concerned to centre our attention on Jesus Christ—these traits are sure signs of ‘enthusiasm’ wherever they are found, even in those whom seem most saintly.

4. Since one can never conclusively prove that any charismatic manifestation is identical with what is claimed as its New Testament counterpart, one can never in any particular case have more than a tentative and provisional opinion, open to constant reconsideration as time and life go on.

The second modern issue that calls for mention is, how should we develop congregational life in our churches so as to secure an ‘every-member ministry’?

____________________________

3‘The air was thick with reports of prophecies and miracles, and there were men of all parties who lived on the border land between sanity and insanity’ (R. Barclay, The Inner Life of the Religious Societies of the Commonwealth, Hodder and Stoughton: London, 1876, p 216). Barclay gives a number of instances.

4 Owen, Works, IV:518.

5 See B.B. Warfield, Miracles Yesterday and Today (Banner of Truth: London, 1967), chap I.

6 Matthew Henry calls tongues ‘the most useless and insignificant of all these gifts’ (on 1 Cor 12:28). It is unlikely that Owen would have quarreled with this verdict.

The New Testament pictures the local church as a body in which every member—that is, literally ‘limb’—has its own part to play in advancing the welfare and growth of the whole. But the churches we know today have inherited over-centralized patterns of life, so that most congregations contain passengers, and our institutional rigidity inhibits our impact on local communities. We are coming increasingly to see that small-group patterns of fellowship, prayer, study, and Christian action—meetings, ‘cells’ and the like—need to be developed within our congregations on a much larger scale than we have done hitherto. Again we ask, can the Puritans help us here? Again the reply is, only indirectly; for over-centralization was not a Puritan problem, and the strength and influence of the family as a religious unit in Puritan times made the quest for other small-group structures less pressing.

However, though the Puritans give us no blue-print for modern group meetings, we find them vindicating with emphasis the fact that such meetings are right, desirable, and beneficial. Thus Owen, for one, included in his first book, The Duties of Pastors and People Distinguished (1643),7 a chapter entitled ‘Of the liberty and duty of gifted uncalled Christians in the exercise of divers acts of divine worship’, in which he argued that

for the improving of knowledge, the increasing of Christian charity, for the furtherance of a strict and holy communion of that spiritual love and amity which ought to be among the brethren, they may of their own accord assemble together, to consider one another, to provoke unto love and good works, to stir up the gifts that are in them, yielding and receiving mutual consolation by the fruits of their most holy faith.8Christians may rightly meet to pray together (cf Acts 12:12), and to minister to each other encouragement (cf Mal 3:16) and spiritual help (cf Is 50:5; Ja 5:16). The only provisos are that they should not become a splinter group, withdrawing from the church’s public worship, or despising and disregarding their pastors, or taking up with doctrinal and expository novelties. Owen ridicules the idea that such gatherings had the nature of ‘schismatic conventicles’, affirming them rather to be lawful and proper means whereby Christians ‘may help each other forward in the knowledge of godliness and the way towards heaven’.9

It is the loss of those spiritual gifts, which hath introduced among many an utter neglect of these duties, so as that they are scarce heard of among the generality of them that are called Christians. But, blessed be God, we have large and full experience of the continuance of this dispensation of the Spirit, in the eminent abilities of a multitude of private Christians . . . some, I confess, they [gifts] have been abused: some have presumed on them beyond the line and measure which they have received; some have been puffed up with them; some have used them disorderly in churches and to their hurt; some have boasted of what they have not received;—all which miscarriages also befell the primitive churches. And I had rather have the order, rule, spirit, and practice of those churches that were planted by the apostles, with all their troubles and disadvantages, than the carnal peace of others in their open degeneracy from all those things.10The book is dated 1644, but Owen elsewhere states that this was the printer’s deliberate mistake (Works, XIII:222).

___________________________

8 Ibid, XIII:44f.

9 Ibid, p 47.

10 Ibid, IV:518.

It is clear that, were Owen with us today, he would be urging us by all means to seek a recovery of ‘every-member ministry’, through a renewed quest for the ‘best gifts’ of the Holy Spirit.

What we have cited from Owen has already made plain the nature of his concern about spiritual gifts. It is an aspect of the consuming, comprehensive concern that marked him all his days—his concern, that is, for authenticity of church life. In pursuing this concern, he appears as at once a reforming theologian, opposing false structures, dead formalism, and unspiritual disorder; a pastoral theologian, challenging distortions of the gospel, mechanical religious routines, and barren professions of faith; and a Christ-centered theologian, insisting throughout that the honour of the Saviour was directly bound up with the state of the visible church. (All of which is only to say that Owen appears as a true Reformed theologian, a kindred spirit to Calvin himself.) The relevance of spiritual gifts to this concern, in Owen’s view, was simply that there can be no authentic church life without their exercise. On this he is explicit and emphatic.

Gifts of the Spirit, says Owen at the outset of his Discourse, are ‘that without which the Church cannot subsist in the world, nor can believers be useful unto one another and the rest of mankind, unto the glory of Christ, as they ought to be’.11 Gifts are ‘the powers of the world to come’ referred to in Hebrews 6:5, and ‘the ministration of the Spirit’ mentioned in 2 Corinthians 3:8—for ‘the promises of the plentiful effusion of the Spirit under the New Testament frequently applied to him as he works evangelical gifts extraordinary and ordinary in men’,12 and the use of his gifts is ‘the great means whereby all grace is ingenerated and exercised’.13 Thus gifts are truly ‘the great privilege of the New Testament.’14

Gifts of the Spirit give the church its inward organic life and its outward visible form. ‘This various distribution of gifts [i.e., that referred to in 1 Corinthians 12:16-25] . . . the Church an organical body; and in this composure, with the peculiar uses of the members of the body, consists the harmony, beauty, and safety of the whole.’15 ‘That profession which renders a Church visible according to the mind of Christ, is the orderly exercise of the spiritual gifts bestowed on it, in a conversation evidencing the invisible principle of saving grace.’16

______________________

11 Ibid, p 420f.

12 Ibid, p 432.

13 Ibid, p 421.

14 Loc cit.

15 Ibid, p 428.

16 Loc cit.

Gifts of the Spirit were, and are, Christ’s sole weapons for setting up, extending, and maintaining his kingdom.

It is inquired what power the Lord Christ did employ . . . erecting of that kingdom or church-state, which being promised of old, was called the world to come, or the new world… I say, it was these gifts of the Holy Ghost. . . . them it was, or in their exercise, that the Lord Christ erected His empire over the souls and consciences of men, destroying both the work and kingdom of the devil. It is true, it is the word of the gospel itself that is the rod of his strength which is sent out of Sion to erect and dispense his rule: but that hidden power which made the word effectual in the dispensation of it, consisted in these gifts of the Holy Ghost.17 By these gifts doth the Lord Christ demonstrate His power, and exercise His rule.18One secret of the abundance of life enjoyed by the early church was that ‘all gospel administrations were in those days avowedly executed by virtue of spiritual gifts’.19 Without gifts, the church is a mere shadow of itself. The round of worship becomes sterile, for ‘gospel ordinances are found to be fruitless and unsatisfactory, without the attaining and exercising of gospel gifts’.20 The church falls into the ditch of formalism and the mire of superstition. Unconcern about gifts, writes Owen,

was that whereby in all ages countenance was given unto apostasy and defection from the power and truth of the gospel. The names of spiritual things were still retained, but applied to outward forms and ceremonies, which thereby were substituted insensibly into their room, to the ruin of the gospel in the minds of men.21 As the neglect of internal saving grace, wherein the power of godliness doth consist, hath been the bane of Christian profession as to obedience . . . the neglect of these gifts hath been the ruin of the same profession as to worship and order, which hath thereon issued in fond superstitions.22________________________

17 Ibid, p 479f.

18 Ibid, p 426.

19 Ibid, p 471.

20 Ibid, p 421.

21 Ibid,, p 423.

22 Ibid, p 421f.

Owen judged the Church of Rome to be a case in point:

We have an instance in the Church of Rome, what various, extravagant, and endless inventions the minds of men will put them upon to keep up a show of worship, when by the loss of spiritual gifts spiritual administrations are lost also. This is that which their innumerable forms, modes, sets of rites and ceremonies, seasons of worship are invented to supply, but to no purpose at all; but only the aggravation of their sin and folly.23

devoid of spiritual gifts is sufficient evidence

of a Church under a degenerating apostasy’,

suggests thoughts that might well disturb

Protestants, too, at the present time.

The overall thrust of Owen’s thinking, and the theological and practical importance for him of the question of gifts, is now clear. In the light of this, we may profitably go on to focus attention on four specific subjects: the nature of spiritual gifts; their place in church life; the different kinds of gifts, ordinary and extraordinary; and the place of gifts in the economy of grace. These themes will occupy the rest of our study.

1. The Nature of Spiritual Gifts

Spiritual gifts are abilities bestowed and exercised by the power of God; not natural, therefore, but supernatural; not human but divine. Owen starts the argument of his Discourse by reviewing the New Testament phraseology for spiritual gifts, observing that this of itself tells us a good deal about their nature. The words may be arranged in four groups (Owen arranges them in three, lumping together the last two). Group one points to the thought that the gifts are free and undeserved bestowals. The words here are dorea and domata, ‘present’ and ‘presents’, and charismata, from charis (grace), on which Owen comments: ‘It is absolute freedom in the bestower of them that is principally intended in this name.’25 Group two highlights the thought that the author of these abilities is the Holy Spirit. Key words here are pneumatika, literally ‘spirituals’, in 1 Corinthians 12:1, and the phrases ‘manifestation of the Spirit’ in verse 7 and ‘distributions of the Holy Ghost’ in Hebrews 2:4 (KJV and RV margin). Group three expresses the idea that a gift is actually God’s work in a man, not the actualizing of a human capacity but a dynamic divine operation. This thought is focused in the word energemata, ‘operations’, literally ‘effectual workings’ (1 Cor 12:6). Group four pinpoints the function which gifts fulfill: they are ‘ministrations’, ‘activities of service’ (1 Cor 12:5), ‘powers and abilities whereby some are enabled to administer spiritual things unto the benefit, advantage, and edification of others’.26

A one-sentence definition of a gift, in line with Owen’s analysis, would be this: a spiritual gift is an ability, divinely bestowed and sustained, to grasp and express the realities of the spiritual world, and the knowledge of God in Christ, for the edifying both of others and of oneself. This definition appears to be entirely scriptural. However, it must be noted that whereas Paul, in directing Christians to use their gifts, speaks of expressing one’s knowledge of God’s mercy in Christ by the way one gives, rules, loves one’s brethren, and shows hospitality, as well as by prophesying, teaching, and exhorting (Rom 12:4-13), Owen conceives of ordinary gifts (as distinct from those, like miracles and tongues, which ‘consisted only in a transient operation of an extraordinary power’) solely in terms of having thoughts of divine things, with power to voice them in words. He does not treat any other capacity for service as a ‘gift’ at all. This intellectualism comes out in his assertion that ‘spiritual gifts are placed and seated in the mind or

_________________________

23 Ibid, p 507.

24 Ibid, p 482.

25 Ibid, p 423.

26 Ibid, p 242.

understanding only . . . they are in the mind as it is notional and theoretical, rather than as it is practical. They are intellectual abilities and no more.’27 This appears to have been the general Puritan view; it rested on the assumption that 1 Corinthians 12:7-11 is a complete enumeration of all the gifts there are, or ever were—an assumption which Chapter IV of the Discourse shows that Owen shared. But the assumption is improvable, and Owen’s view is surely at this point incomplete. Has Paul only intellectual abilities in view when he says that God has set in the church ‘helps’ and ‘governments’ (1 Cor 12:28)? Significantly, perhaps, Owen makes no reference to these either in the Discourse or, so far as I can find, in any of his writings on the local church; probably, like other Puritan expositors, he did not suppose that the functions to which these names referred were manifestations of a distinct spiritual gift at all.28 But it seems clear that the category of spiritual gifts, as Paul views it, includes graces of character and practical wisdom, as well as powers of theoretical reasoning and discourse about divine truths.

Gifts are bestowed by the Lord Jesus Christ (Eph 4:8) through shedding forth on men the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:23). Owen equates the ‘power’ of the Spirit in Acts 1:4, 1 Corinthians 2:4 with the bestowal and exercise of gifts. Though gifts are often given through sanctification of natural abilities, they are not natural abilities, and sometimes this is marked by non-development in Christians of the gifts that their natural abilities would lead one to expect, and the manifesting in them of gifts for which their natural powers gave no foundation at all. But all gifts alike are increased by use of the means of grace—prayer, meditation, constant self-abasement, and active service in God’s cause.

2. Spiritual Gifts and Ecclesiastical Office

Though, as we saw, Owen recognizes that Christ gives gifts to all, and that the local church should accordingly display a pattern of ‘every member ministry’ in its regular life, the official ministry is central in Owen’s interest, and it is in terms of the relation and distinction between gifts and ecclesiastical office that he expounds (in Chapters III to VIII of the Discourse) the place of the gifts in the church. He begins by analyzing the notion of ‘office’ in terms of power plus duty (in the sense of defined responsibility). He declares that ‘ecclesiastical office is an especial power given by Christ unto any person or persons for the performance of especial duties belonging unto the edification of the Church in an especial manner’.29 He affirms the standard Reformed view of ordination as an act of Christ conferring office through the action of the church, rather than as an act of the church delegating to the ordained its own inherent powers. He also sets forth exactly the standard Reformed distinction between the offices of apostle, evangelist, and prophet, which were temporary and extraordinary, ceasing with the apostolic age, and the office of presbyter, which is permanent and ordinary, and is to last till the Lord returns. Laying down the principle that ‘all office-power depends on the communication of gifts, whether extraordinary or

___________________________

27 Ibid, p 437.

28 ‘Helps’ and ‘governments’ were not identified with certainty by any Puritan exegete. Matthew Pool (Annotations, 1685 ad loc) confessed it ‘very hard to determine’ who they were—‘whether he meaneth deacons, or widows . . . as helpful in the case of the poor, or some that assisted the pastors in the government of the church, or some that were extraordinary helps to the apostles in the first plantation of the church.’ Matthew Henry thought ‘helps’ were sick visitors, and ‘governments’ were, in effect, deacons, or ‘poor stewards’ in the old Methodist sense, distributing the church’s charitable gifts to the needy. Richard Baxter thought ‘helps’ were ‘eminent Helpers of the Churches by Charity and special Care, especially for Ministers and the Poor; Governments to arbitrate Differences and keep Order’ (Paraphrase of the New Testament, ad loc). None of these writers, however, nor any other Puritan so far as I know, thought of a gift of helping and governing.

29 Owen, Works, IV:438. ordinary’,

ordinary30, he argues that extraordinary gifts presupposed both an extraordinary call and extraordinary gifts, and that in the absence of the latter, no less than of the former, it is impossible that the apostles, the evangelists (whom he understands to have been the apostles’ personally appointed assistants), and the prophets could have successors today.31 All this is familiar ground to those who have read Calvin’s Institutes IV:iii, and therefore we need not stay on it. Owen’s adoption of Independent principles of polity did not affect in the least his adherence to Presbyterian principles regarding ministerial order, character, and authority.

Nor is he anything other than typical of the whole Reformed tradition when he declares that ‘spiritual gifts of themselves make no man actually a minister, yet no man can be made a minister according to the mind of Christ, who is not partaker of them’.32 His point is that a minister is Christ’s gift to the church (Eph 4:8) only because, and in so far as, he is gifted by Christ for ministry in his Master’s name, and the church has no right to call and send into the Lord’s vineyard men whose gifts do not warrant the confidence that the Lord himself has called them to this service.

The Church hath no power to call any unto the office of the ministry, where the Lord Christ hath not gone before it in the designation of him by an endowment of spiritual gifts; for if the whole authority of the ministry be from Christ, and if he never give it but where he bestows these gifts with it for its discharge, as in Ephesians 4:7, 8, etc., then to call any to the ministry whom he hath not so previously gifted is to set him aside, and act in our own name and authority.33The main application of our Lord’s parable of the talents, in Owen’s view, is to the ordained ministry, and its main lesson is that ‘wherever there is a ministry in the Church that Christ owneth or regardeth as used and employed by him, there persons are furnished with spiritual gifts from Christ by the Spirit, enabling them unto the discharge of that ministry; and

_________________________

30 Ibid, p 442.

31 Owen’s remarks on prophets in the New Testament are worth noticing:

The names of prophet and prophecy are used variously in the New Testament: for, 1. Sometimes an extraordinary office and extraordinary gifts are signified by them; and, 2. Sometimes extraordinary gifts only; and, 3. Sometimes an ordinary office with ordinary gifts, and sometimes ordinary gifts only. And unto one of these heads may the use of the word be everywhere reduced.32 Ibid, p 494.

1. In the places mentioned (Eph 4:11; 1 Cor 12:28) extraordinary officers endued with extraordinary gifts are intended. . . . And two things are ascribed unto them: (1) that they received immediate revelations and directions for the Holy Ghost’ [Owen cites Acts 13:2]; (2) They foretold things to come (Acts 11:28ff; 21:10f.

2. Sometimes an extraordinary gift without office is intended (Acts 21:9; 19:6; 1 Cor 14:29-33).

3. Again, an ordinary office with ordinary gifts is intended by this expression (Romans 12:6 — prophecy here can intend nothing but teaching or preaching, in the exposition and application of the word; for the external rule is given unto it, that it must be done according to the ‘proportion of faith’, or the sound doctrine of faith revealed in the Scriptures). Hence also those who are not called unto office, who have yet received a gift enabling them to declare the mind of God in the Scripture unto the edification of others, may be said to ‘prophesy’ (Works, 451f).

33 Ibid, p 495.

where there are no such spiritual gifts dispensed by him, there is no ministry that he either accepteth or approveth’.34

3. Ordinary and Extraordinary Gifts

The last point leads on to the question, what gifts are required for the ordinary presbyteral ministry? Owen’s answer is, not the extraordinary gifts mentioned in 1 Corinthians 12:5-11 (faith that works miracles, healing powers, immediate discernment of spirits, tongues, and interpretation of tongues), but the ordinary ones, wisdom and knowledge at an extraordinary pitch. Ministers must be able ‘in an eminent degree’ (Owen’s constant phrase) to preach the word with application, to pray with unction, and to rule with wisdom. To speak to men for, and from, God, and to speak to God for, and as the mouthpiece of, God’s flock, is no small undertaking. For it, says Owen, men need three gifts in particular.

The first gift is ‘wisdom, or knowledge, or understanding’:

such a comprehension of the scope of the Scripture and of the revelation of God therein; such an acquaintance with the systems of particular doctrinal truths, in their rise, tendency, and use; such a habit of mind in judging of spiritual things, and comparing them one with another; such a distinct insight into the springs and course of the mystery of the love, grace, and will of God in Christ, as enables them in whom it is to declare the counsel of God, to make known the way of life, of faith and obedience, unto others, and to instruct them in their whole duty to God and man therein.35Then, secondly, ‘with respect unto the doctrine of the gospel . . . is required . . . to divide the word aright, which is also a peculiar gift of the Holy Ghost, (2 Tim 2:15).’36 This gift of ‘right dividing’ Owen understands, not in the exotic latter-day sense of distinguishing dispensations, but in the standard Puritan sense of making appropriate application of God’s truth to the condition of individuals. Whether, as Owen, with Calvin, believed, the picture here is of discriminating distribution of food to the family, rather than, as most modern expositors hold, cutting a straight furrow, is not the main issue; the central question is rather, will a minister be approved by God as a good workman, handling the word of truth in a manner appropriate to its nature and purpose, and winning the praise of the God whose word it is, if he misapplies it, or fails to apply it at all? One of the most valuable elements in Puritan teaching on the ministry is the constant stress laid on the need for discerning and discriminating application. Owen lays out in detail what this requires of a man:

__________________________

34 Ibid, p 505.

35 Ibid, p 509.

36 Ibid, p 510.

(1) A sound judgment in general concerning the state and condition of those unto whom any one is so dispensing the word. It is the duty of a shepherd to know the state of his flock; and unless he do so, he will never feed them profitably. He must know whether they are babes, or young men, or old; whether they need milk or strong meat . . . in the judgment of charity they are converted unto God, or are yet in an unregenerate condition; what probably are their principal temptations, their hindrances and furtherances; what is their growth or decay. (2) An acquaintance with the ways and methods of the work of God’s grace on the minds and hearts of men, that he may pursue and comply with its design in the ministry of the word . . . is unacquainted with the ordinary methods of the operation of grace fights uncertainly in his preaching of the word like a man beating of the air. It is true, God can, and often doth, direct a word of truth, spoken as it were at random, unto a proper effect of grace, on some or other, as it was when the man drew a bow at a venture, and smote the king of Israel between the joints of the harness. But ordinarily a man is not likely to hit a joint, who knows not how to take his aim. (3) An acquaintance with the nature of temptation . . . things might be added on this head. (4) A right understanding of the nature of spiritual diseases, distempers, and sicknesses, with their proper cures and remedies, belongeth hereunto. For the want hereof the hearts of the wicked are oftentimes made glad in the preaching of the word, and those of the righteous filled with sorrow; the hands of sinners are strengthened, and those who are looking towards God are discouraged or turned out of the way.37The question of the best syllabus of study for ministerial candidates is often discussed today. Would it not be in our interest to reconsider this syllabus of Owen’s? How dare we, in this or any age, contemplate ordaining men who have not first mastered it?

Thirdly, with knowledge of God’s truth and skill to apply it must go the gift of utterance, which, says Owen, ‘is particularly reckoned by the apostle among the gifts of the Spirit’ (1 Cor 1:5; 2 Cor 8:4; cf Eph 6:19; Col 4:3).38 This is not the same as rhetorical skill, or a pretty wit, or ‘a natural volubility of speech, which . . . so far from being a gift of the Spirit . it is usually a snare to them that have it, and a trouble to them that hear them’; it consists of naturalness appropriate to the subject-matter, plus ‘boldness and holy confidence’, plus gravity and ‘that authority which accompanieth the delivery of the word when preached in demonstration of these spiritual abilities.’39 ‘All these things are necessary,’ Owen concludes, ‘that the hearers may receive the word, not as the word of man, but as it is indeed the word of God.’

This rather shattering list of qualifications needed for acceptable ministry prompts the cry, ‘who is sufficient for these things?’ This leads us straight to our final topic:

4. Gifts and Grace

Owen’s concern for authenticity and reality in the life of the church and of Christians prompts him, when discussing the relation of gifts and grace in Chapter II of the Discourse, to lay stress on the negative point that a man can have gifts without grace—that is, one can be skilled in Christian comprehension and communication without having been born again. Owen insists that here are two distinct types of operation by the Spirit of God, and that only the work of grace, producing ‘the fruit of the Spirit’ in a renewed heart and a transformed character, is saving. Gifts belong to the outward administration of the covenant of grace only; it does not follow that a man with spiritual abilities is therefore in the inward saving relationship with God at which the covenant aims. The thrust of this is that none may presume on his gifts, and conclude from his having theological interests and abilities that therefore he has eternal life; it does not follow. Only the man who has come to know his sin and has been led in repentance

_________________________

37 Ibid, p 510f.

38 Ibid, p 512.

39 Ibid, p 512f.

and faith to the cross of Christ is in grace; a merely gifted man, however theologically articulate, may be under wrath still. The need to make this point, in our day as in Owen’s, is too obvious to require emphasis from me. We should thank Owen for reminding us of it—and examine ourselves.

But there is another side to the picture, a word of encouragement and incentive to balance the word of warning. Where ‘saving graces and spiritual gifts . . . bestowed on the same persons,’ writes Owen,

they are exceedingly helpful unto each other. A soul sanctified by saving grace, is the only proper soil for gifts to flourish in. Grace influenceth gifts unto a due exercise, prevents their abuse, stirs them up unto proper occasions, keeps them from being a matter of pride or contention, and subordinates them in all things unto the glory of God. When the actings of grace and gifts are inseparable, as when in prayer the Spirit is a spirit of grace and supplication, the grace and gift of it working together, when utterance in other duties is always accompanied with faith and love, then is God glorified, and our own salvation promoted. Then have edifying gifts a beauty and lustre upon them, and generally are most successful, when they are clothed and adorned with humility, meekness, a reverence of God, and compassion for the souls of men.40Do we deplore that so little of the life of God appears in our souls? Is it our complaint that our gifts are so small? Use your gifts and graces, such as they are, to stir each other up to exercise, Owen is saying, and you will have more of both. Do we seek to grow in grace through the exercise of our gifts? When we speak to others of the things of God, do we seek to feed our own souls on the same truths? Equally, do we seek to increase our gifts through stirring up our hearts to seek God? When we speak of divine things to others, and lead them in prayer, do we seek to feel the reality of the things we speak of? Small gifts may have great usefulness when backed by honest, sincere feeling and unaffected holiness. Are we depressed about our Christian service, finding it largely barren and ourselves largely impotent? Let us go back to our God for wisdom to learn how his grace and gifts in us may help each other. Covet earnestly the best gifts — and with them a humble, loving heart. This is the way of growth and fruitfulness.

___________________________

40 Ibid, p 438.

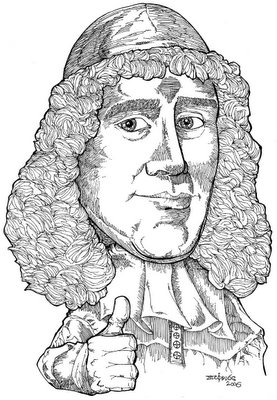

of his most excellent drawings: this one being of Dr. John Owen.

We are blessed on this blog to be able to feature some of Stephen's great talent.

Used by permission of Crossway Books, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers, Wheaton, IL 60187, Crossway

6 comments:

Quick post to say thank you for this!! (P.F. Chang's is beckoning, but as soon as I return, I'm going to read it with the attentiveness and focus it requires).

Kudos....

--Steph

Two pillars of the Church for sure: John Owen, and Dr. Packer.

Good reading, and quite deep for me.

Thanks. I appreciate the wisdom from these two great men of God.

Now I'm off to see King Kong.

Steve,

I haven't read the article yet, but Steve Hesselmen's blog is at

http://hesselblog.blogspot.com/

I agree... Sola Scriptura must mean something in this discussion.

Dr. MacArthur has some excellent material on this issue which you can locate through google; if you also go to monergism.com and look under their subjects on cessationism, they have quite a bit as well.

Also, re-read the Westminster Confession - some very good insights.

Grace and peace to you,

Steve

Steve,

Packer, speaking of Owen, says,

"He [Owen] also sets forth exactly the standard Reformed distinction between the offices of apostle, evangelist, and prophet, which were temporary and extraordinary, ceasing with the apostolic age, and the office of presbyter, which is permanent and ordinary, and is to last till the Lord returns."

Owen was correct regarding the ceasing of the office of "apostle" and "prophet", though I don't see why the office of "evangelist" would also fall in this category of "ceased".

Eph. 2:20 says that the Church (household of God) was "built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone (Eph. 2:20)."

After that foundation was build, I don't see any biblical warrant for the office of "evangelist" to have been done away with. And in fact, if it were done away with, it probably would have been included in the Eph. 2:20 "foundation".

In any case, Owen is correct that spiritual gifts are "necessary" for the operation of the Body of Christ, but he of course can't mean those "sign gifts" such as revelatory (new revelation) gifts, or the doing of miracles, since Packer admits that they were not in operation in Owen's or other Puritan's churches.

I always love reading from the pens of Owen and Packer...

If you haven't read Owen on the Holy Spirit in his book.... "The Holy Spirit" - I highly recommend it. Nourishment for the soul...

Post a Comment